It’s in the nature of cities to be absorbing, overwhelming places. Built from the ground- up over hundreds of years, it’s impossible to avoid getting sucked into the looming tangles of buildings and bus routes, the noise, light and superhuman heat. Eventually and invariably people themselves become part of the manic whirling rhythm of cities, which is how a city goes about making itself your home. There are benefits to this, of course – knowing the best late-night spots to find fun and solace, ensuring those bus routes don’t leave you stranded miles from bed in the pouring rain – but as more time in the chaos accrues it’s tough not to lose your sense of perspective, an idea of what the city looks like to those outside. Often, the only time we see our cities for what they really are is when we go away and glance at them from a distance. Often, we best appreciate our cities as we hover in holding patterns over hometown airports, peering down at the array of lights below.

Rejjie Snow was 17 when he left home in Dublin to embark on a soccer scholarship at a prep school in Atlanta, Georgia. To him, growing up in the Irish capital wasn’t a paradise exactly but it was a place that shaped the rapper – real name Alex Anyaegbunam – in ways that he didn’t really recognise till he moved to the States. “As soon as I got there, I. started seeing the side of Dublin that I love. I missed it a lot,” he explains. “Being in America was cool; I learned so much and it gave me loads of confidence and trust in myself, but it also kind of taught me just how unique Dublin is, and how hard it is to find that same hometown familiarity elsewhere.”

Rejjie’s soccer scholarship took in one year of high school and 18 months of college before he felt the urge to break away and pursue music instead. If deciding to leave everyone you know behind and move to another continent at 17 is a big step, then dropping all of that to go home and forge a path in music at 20 is an even bigger one, but it’s a step that’s paying off.

May 03, 2019

A Love Letter To Dublin

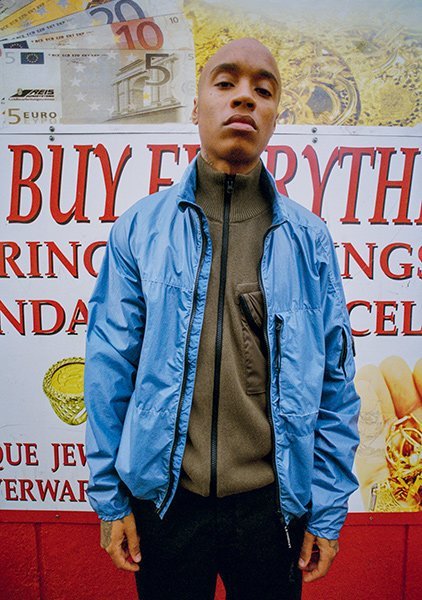

Even at this early stage, Rejjie is the biggest rapper Ireland has ever produced, a 25-year-old who grew up in North Dublin’s Drumcondra suburb but whose talent saw him cherrypicked by 300 Entertainment, the US label famed for their work with the likes of Migos and Young Thug. February’s debut album Dear Annie is an engaging, kaleidoscopic cruise through electro- funk, neo-soul, smart hip-hop and nocturnal jazz, laden with effortless pop hooks and guided by Rejjie’s American inflected Irish brogue. While much of the music sounds pulled out of left-field, there’s an undeniable sense of star- quality showmanship to it; it feels like an album that should be delivered from a rotating, circular stage, peopled by a supporting cast of musicians, wingmen and muses.

If the vast majority of Rejjie’s musical influences, contemporaries and collaborators are American, the personality that sets his music apart from the pack is one that was built in Dublin. Born there in 1993 to a Nigerian father and Irish- Jamaican mother, Rejjie’s first exposure to hip- hop came via the cousins he shared a house with in Drumcondra. “Everything I learned about manhood, I learned from my cousins,” he says. “We’d do everything together: go out, play ‘knick-knack’ [knocking on strangers’ front doors then running away], throw eggs at houses, all that teenage stuff. One of my cousins was already rapping, he was the first person I saw doing music. I looked up to him, so he’d show me how to write lyrics, explain what a 16-bar was, that kind of thing.”

His earliest lyrics, he says, “were just about killing people and drugs, the usual cliches”, but gradually Rejjie started to find inspiration in the reality of the life he’d returned to in Dublin.

If the vast majority of Rejjie’s musical influences, contemporaries and collaborators are American, the personality that sets his music apart from the pack is one that was built in Dublin. Born there in 1993 to a Nigerian father and Irish- Jamaican mother, Rejjie’s first exposure to hip- hop came via the cousins he shared a house with in Drumcondra. “Everything I learned about manhood, I learned from my cousins,” he says. “We’d do everything together: go out, play ‘knick-knack’ [knocking on strangers’ front doors then running away], throw eggs at houses, all that teenage stuff. One of my cousins was already rapping, he was the first person I saw doing music. I looked up to him, so he’d show me how to write lyrics, explain what a 16-bar was, that kind of thing.”

His earliest lyrics, he says, “were just about killing people and drugs, the usual cliches”, but gradually Rejjie started to find inspiration in the reality of the life he’d returned to in Dublin.

"Dublin isn’t like anywhere else in the world"

“It didn’t make sense to mimic American rappers ‘cos Dublin isn’t like anywhere else in the world; it’s a whole different reality. As I got older I started talking about that. It’s so unique, and people always wanna hear or see something new. The shit around me is an inspiration in itself.” That “unique reality” finds perhaps its most vivid expression in the videos for Rejjie’s tracks ‘Virgo’ and ‘Flexin’, which feature pale, shorn kids floating on liloes in Dublin’s Royal Canal, locals riding horses and scrambler bikes across inner-city estates and basketball courts, joyridden cars weaving in donuts and burning up outside a branch of the Irish bed retailer Mattress Mick’s.

His Irish upbringing also comes through in lyrics that revel and rejoice in their familiar references to teenage house parties, graffiti raids, hard booze and soft drugs; you imagine that Rejjie is the only rapper ever signed to 300 Entertainment with bars about the IRA, playingFIFA and manses, the name for the ecclesiastical dwellings inhabited by religious ministers in Ireland. The strongest reverence on Dear Annie, though, is reserved for women, and love and sex with women: “Going out to parties in Dublin and discovering girls opened up a whole new world to my art, expression, inner feelings and stuff... the house I grew up in was very cold in that sense; I wouldn’t have been able to express myself emotionally, so girls gave me someone to talk to about how I felt.”

His Irish upbringing also comes through in lyrics that revel and rejoice in their familiar references to teenage house parties, graffiti raids, hard booze and soft drugs; you imagine that Rejjie is the only rapper ever signed to 300 Entertainment with bars about the IRA, playingFIFA and manses, the name for the ecclesiastical dwellings inhabited by religious ministers in Ireland. The strongest reverence on Dear Annie, though, is reserved for women, and love and sex with women: “Going out to parties in Dublin and discovering girls opened up a whole new world to my art, expression, inner feelings and stuff... the house I grew up in was very cold in that sense; I wouldn’t have been able to express myself emotionally, so girls gave me someone to talk to about how I felt.”

The “only black kid at school”, Rejjie’s school years weren’t exactly straightforward. Describing himself repeatedly as “the black sheep”, he views Dublin as a place where a young man can “either go left or right” but says that the seriousness with which he took his nascent football career and graffiti “kept me out of serious trouble”.

“I was shy but started going out quite young, I snuck into my first rave at about 14,” he remembers. “I’d drink then, too – cans in the park, the usual. There’d be drugs about at house parties, but I wouldn’t really get involved. I was too into football and didn’t want to jeopardise that. Until I went to America, I was very disciplined within myself.” Football and graffiti also served as gateways into an interest in fashion that is still borne out today in the way he dresses, a collision of the latest US sportswear and classic UK street style forged in his early experiences of Dublin’s terraces and rail depots.

“I’d go to football games here and everyone was wearing C.P. Company. That was the first time I was introduced to it. As a kid you’d gravitate towards that – you’d see people wearing CP and it felt like it gave them some stature. I remember being about 11 and seeing the goggles on the hoods and being amazed by it.”

Where he once took cues from older cousins, football casuals and train taggers, now Rejjie finds himself in a position where he’s become a figurehead of an Irish hip-hop scene that, before he came along, wouldn’t have been considered by many as especially credible.

“I was shy but started going out quite young, I snuck into my first rave at about 14,” he remembers. “I’d drink then, too – cans in the park, the usual. There’d be drugs about at house parties, but I wouldn’t really get involved. I was too into football and didn’t want to jeopardise that. Until I went to America, I was very disciplined within myself.” Football and graffiti also served as gateways into an interest in fashion that is still borne out today in the way he dresses, a collision of the latest US sportswear and classic UK street style forged in his early experiences of Dublin’s terraces and rail depots.

“I’d go to football games here and everyone was wearing C.P. Company. That was the first time I was introduced to it. As a kid you’d gravitate towards that – you’d see people wearing CP and it felt like it gave them some stature. I remember being about 11 and seeing the goggles on the hoods and being amazed by it.”

Where he once took cues from older cousins, football casuals and train taggers, now Rejjie finds himself in a position where he’s become a figurehead of an Irish hip-hop scene that, before he came along, wouldn’t have been considered by many as especially credible.

"When I came home and saw how I’d ended up playing a part in other people’s journeys, it really inspired me."

Where previously the youth of Dublin might not have thought of their home city as a place that could produce rappers, perhaps now they look at Rejjie and think, ‘If he can, I can too.’ Is that a role that he’s embraced at all? “Yeah, it took me a while though,” he says, “It made me feel very self- conscious at the start. But when I came home and saw how I’d ended up playing a part in other people’s journeys, it really inspired me. I’m a lot more involved in things going on in Dublin than I used to be. Growing up, I never had any musical figures to look up to, but I’m not afraid of anything and I want people to take that away from what I’m doing, to know that they can be fearless too.”....

READ MORE THIS ARTICLE

WRITTEN BY C.P COMPANY